Introduction

The immune system is an organization of cells, tissues[1] and organs that work together to protect (defend) our body against "foreign" invaders. Initially, these are microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, parasites and fungi. The human body is an ideal environment for many microorganisms, which is why they try to get into it. The job of the immune system is to keep them away and, failing that, to detect and destroy them. When the immune system attacks the wrong target or is damaged (ineffective), it can trigger various diseases, including allergies, arthritis and AIDS.

The immune system is astonishingly complex. He can recognize and remember millions of different enemies, he can produce various substances and cells to mark (match) or erase each of them. The secret of its success is its developed and dynamic communication network. Billions of cells are organized into subgroups and clusters, like swarms of bees circling a hive, passing information back and forth. When the cells of the immune system receive an alarm signal, they undergo a significant change and begin to produce strong chemicals. These substances allow cells to regulate their own growth and behavior. They recruit their allies and direct them to places where the problem occurred.

[1] tissue – a group of similar cells joined together to perform the same function.

Host versus Alien

The key to a healthy immune system is its unique ability to distinguish between the body's own cells - its own and non-self - foreign cells. The body's defenses usually co-exist peacefully with cells that have their own recognition molecules. But as soon as they encounter cells or microorganisms carrying the "alien" marker, they quickly attack.

Anything that can trigger such an immune response is referred to as an antigen. The antigen may be a microorganism, such as a virus, or even a fragment of a bacterium. Tissues or cells from another person (except identical twins) therefore having the designation "foreign" acting as antigens. This explains why a transplant of "foreign" tissue may be rejected.

In certain abnormal situations, the immune system may confuse "self" and "foreign" and launch an attack against its own cells or tissues. This phenomenon (situation) is called an autoimmune disease. For example, certain forms of joint disease and diabetes are autoimmune diseases. In other situations, the immune system may react to foreign, seemingly harmless substances, such as pollen of some plants. The result is an allergy, and this type of antigen is called an allergen.

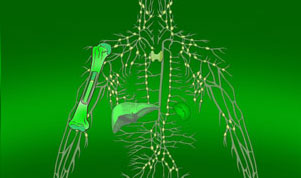

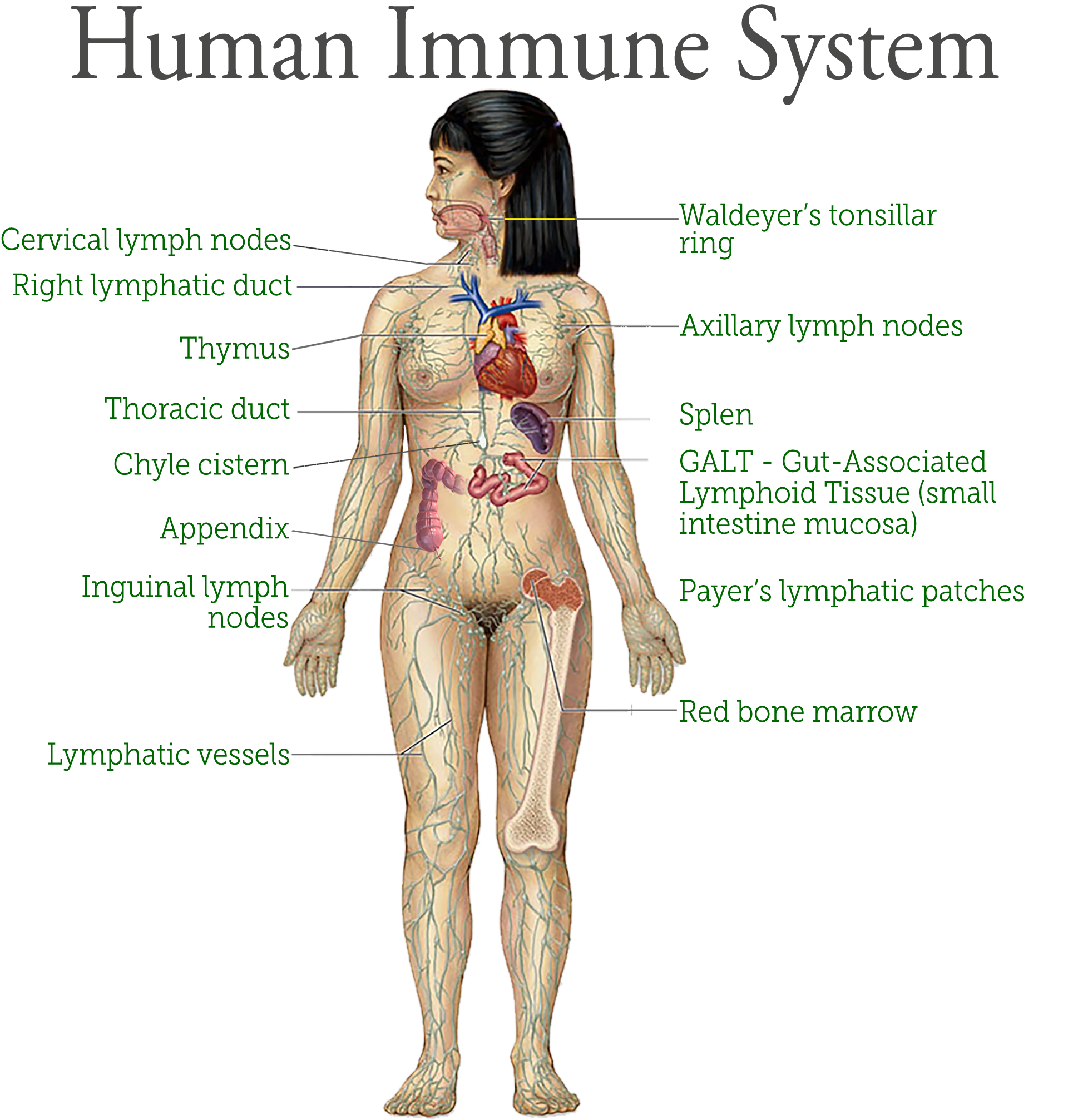

The structure of the immune system

The immune system is the body’s tool for preventing or limiting infection. Its very complex network of cells, organs, proteins, and tissues enable the immune system to defend the body from pathogens.

The organs (components) of the immune system are distributed throughout the body. They are called lymphoid organs because they are the home of lymphocytes – tiny white blood cells (blood cells) that are key players in the immune system.

Bone marrow

Bone marrow it is the soft tissue inside the marrow cavity of bones, is the ultimate source of all blood cells, including white blood cells destined for immune system cells. Bone marrow makes more than 220 billion new blood cells every day. Most blood cells in the body develop from cells in the bone marrow.

Bone marrow is either red or yellow, depending upon the preponderance of hematopoietic (red) or fatty (yellow) tissue. In humans the red bone marrow forms all of the blood cells with the exception of the lymphocytes, which are produced in the marrow and reach their mature form in the lymphoid organs. Red bone marrow also contributes, along with the liver and spleen, to the destruction of old red blood cells. Yellow bone marrow serves primarily as a storehouse for fats but may be converted to red marrow under certain conditions, such as severe blood loss or fever. At birth and until about the age of seven, all human marrow is red, as the need for new blood formation is high. Thereafter, fat tissue gradually replaces the red marrow, which in adults is found only in the vertebrae, hips, breastbone, ribs, and skull and at the ends of the long bones of the arm and leg; other cancellous, or spongy, bones and the central cavities of the long bones are filled with yellow marrow.

Thymus

Thymus is a pyramid-shaped lymphoid organ that, in humans, is immediately beneath the breastbone at the level of the heart. The organ is called thymus because its shape resembles that of a thyme leaf. The primary function of the thymus is to facilitate the maturation of lymphocytes known as T cells, or thymus-derived cells, which determine the specificity of immune response to antigens (foreign substances) in the body.

The thymus gland is most active during childhood. Your thymus actually starts making T-cells before you’re born. It keeps producing T-cells and you have all the T-cells you need by the time you reach puberty. After puberty, your thymus gland slowly starts to decrease in size and is replaced by fat.

Lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are located throughout the body. They are small, bean-shaped glands that play a crucial role in the immune system. During an infection, a person may notice swollen lymph nodes. The body contains hundreds of lymph nodes. They form clusters around the body and are particularly prominent in areas such as the neck, armpit and groin and behind the ears.

Lymph nodes filter lymphatic fluid, which helps rid the body of germs and remove waste products. The body’s cells and tissues dispose of waste products in lymphatic fluid, which lymph nodes then filter. During this process, they catch bacteria and viruses that could harm the rest of the body.

Lymph nodes are an essential part of the body’s immune system. Due to their function, they come into contact with toxins, which can cause them to swell. Although swollen lymph nodes are common, they may occasionally indicate lymph node cancer, or lymphoma.

Spleen

Spleen is an organ of the lymphatic system located in the left side of the abdominal cavity under the diaphragm, the muscular partition between the abdomen and the chest. In humans it is about the size of a fist and is well supplied with blood. As the lymph nodes are filters for the lymphatic circulation, the spleen is the primary filtering element for the blood. The organ also plays an important role in storing and releasing certain types of immune cells that mediate tissue inflammation.

The white pulp of the spleen contains typical lymphoid elements, such as plasma cells, lymphocytes, and lymphatic nodules, called follicles in the spleen. Germinal centres in the white pulp serve as the sites of lymphocyte production. Similar to the lymph nodes, the spleen reacts to microorganisms and other antigens that reach the bloodstream by releasing special phagocytic cells known as macrophages. Splenic macrophages reside in both red and white pulp, and they serve to remove foreign material from the blood and to initiate an immune reaction that results in the production of antibodies.

Lymphoid tissue

Lymphoid tissue consists of many organs that play a role in the production and maturation of lymphocytes in the immune response. Lymphoid tissue may be primary or secondary depending upon its stage of lymphocyte development and maturation. Secondary lymphoid tissue is collections of lymphoid tissue associated with many organs. The secondary lymphoid tissues consist of lymph nodes, tonsils, Peyer’s patches, spleen, adenoids, skin, and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT). Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue types are listed below:

Lymphoid tissue consists of many organs that play a role in the production and maturation of lymphocytes in the immune response. Lymphoid tissue may be primary or secondary depending upon its stage of lymphocyte development and maturation. Secondary lymphoid tissue is collections of lymphoid tissue associated with many organs. The secondary lymphoid tissues consist of lymph nodes, tonsils, Peyer’s patches, spleen, adenoids, skin, and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT). Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue types are listed below:

- GALT (gut-associated lymphoid tissue. Peyer's patches are a component of GALT found in the lining of the small intestines.)

- BALT (bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue)

- NALT (nasal-associated lymphoid tissue)

- CALT (conjunctival-associated lymphoid tissue)

- LALT (larynx-associated lymphoid tissue)

- SALT (skin-associated lymphoid tissue)

- VALT (vulvo-vaginal-associated lymphoid tissue)

- TALT (testis-associated lymphoid tissue)

MALT is populated by lymphocytes such as T cells and B cells, as well as plasma cells, dendritic cells and macrophages, each of which is well situated to encounter antigens passing through the mucosal epithelium. In the case of intestinal MALT, M cells are also present, which sample antigen from the lumen and deliver it to the lymphoid tissue. MALT constitute about 50% of the lymphoid tissue in human body. Immune responses that occur at mucous membranes are studied by mucosal immunology.

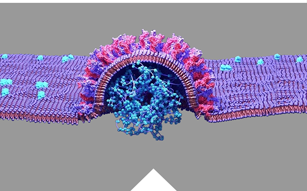

Immune system cells and their products

The immune system accumulates a huge arsenal of cells, not only lymphocytes but also phagocytic cells and their relatives capable of phagocytosing (eating) cells. Certain immune cells catch all invaders, while others are trained on specific targets. To function effectively, most cells need cooperation with their companions. Sometimes immune cells communicate through direct physical contact, sometimes by releasing chemical messengers (transmitters).

The immune system collects just a little of each type of different cell needed to recognize millions of possible enemies. But when a hostile antigen appears, that "handful" of matching cells will multiply into a full army. When their work is finished, most of them will disappear and only a few will remain at the post to guard our body against future attacks.All immune cells start as immature bone marrow stem cells. They respond to various cytokines and other signals to mature into particular ones immune cells such as T or B lymphocytes or phagocytes. Stem cells are not predetermined as to their future development and may constitute an interesting possibility in the treatment of immune system disorders. Currently, it is being investigated whether a person's own stem cells could be used to regenerate the damaged immune response in autoimmune diseases and immunodeficiencies.

Phagocytes are large white cells that can devour and digest microbes and other foreign particles.

Phagocytes are large white cells that can devour and digest microbes and other foreign particles.