Our immune system is one of nature's most fascinating inventions. It easily protects us against billions of bacteria, viruses and other pathogens. Most of us do not realize on a daily basis that our immune system is constantly on the alert to counterattack at the first signal/symptom of the invasion of harmful microorganisms.

The immune system is extremely complex. It consists of many organs, many types of cells and proteins that have different tasks to fight foreign "invaders".

Self and non-self

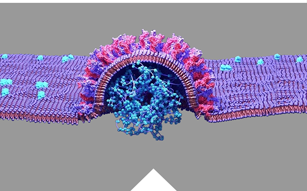

In humans, all nucleated cells express distinctive surface molecules called major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC class I) that identify them as being self. Anything that does not posses these “self tags” may be recognized by the immune system as foreign and targeted. Anything that triggers the immune system is called an antigen.

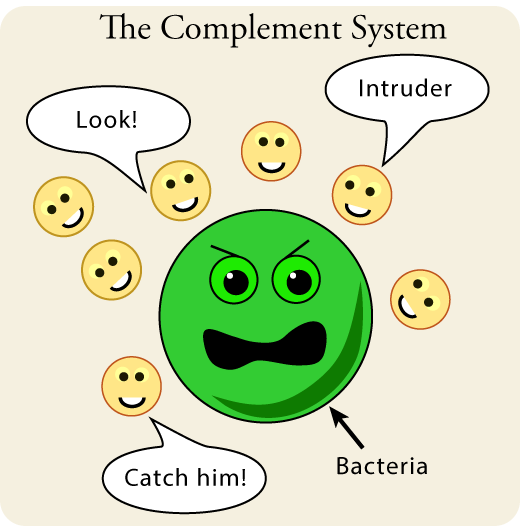

The Complement System

The first line of the immune system that encounters invaders, such as bacteria, is a group of proteins called the complement system. These proteins float freely in the blood and can quickly reach to the affected area, where they can react directly with antigens – molecules recognized as foreign.

When proteins of the complement system are activated, they can:

● Trigger/launch the inflammatory response

● Attract voracious cells such as macrophages to the site

● Adhere1 to the "intruders" so that the phagocytes can more easily destroy them

● Destroy "intruders"

Phagocytes

Phagocyte is type of cell that has the ability to ingest, and sometimes digest, foreign particles, such as bacteria, carbon, dust, or dye. It engulfs foreign bodies by extending its cytoplasm into pseudopods (cytoplasmic extensions like feet), surrounding the foreign particle and forming a vacuole. Poisons contained in the ingested bacteria cannot harm the phagocyte so long as the bacteria remain in the vacuole; phagocyte enzymes are secreted into the vacuole in which digestion takes place. There are three main types of phagocytes: neutrophiles, macrophages and dendritic cells.

|

Neutrophiles – a type of immune cell found in blood. They often constitute the first line of defense during infection. They attack all "intruders" and "bite" them until they destroy them. Pus from infected wounds usually contains dead granulocytes. In addition, a small part of the granulocyte population is specialized to attack larger parasites such as worms. |

|

Macrophages ("big eaters") respond to invasion slower than granulocytes, but they are larger, live longer and have much greater capabilities. Macrophages also play a key role in alerting other parts of the immune system2. They come from white blood cells called monocytes, which transform into macrophages when they pass from the blood into the tissues. |

|

Dendritic cells – A special type of immune cell that is found in tissues, such as the skin, and boosts immune responses by showing antigens on its surface to other cells of the immune system. A dendritic cell is a type of phagocyte and a type of antigen-presenting cell (APC). And like macrophages, dendritic cells help activate the entire immune system2. They can cleanse body fluids of foreign particles and microorganisms. |

Lymfocytes – T cells and B cells

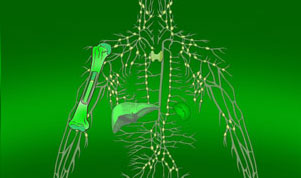

Lymphocytes are white blood cells (leukocytes) and come from the bone marrow, but they migrate to different parts of the lymphatic system, such as the lymph nodes, spleen or thymus. There are two main types of lymphocytes: T cells and B cells. The lymphatic system also includes a transport system - the lymphatic vessel system - used to transport and store lymphocytes. The lymphatic system supplies lymphocytes to our body and filters tissues from dead cells and microorganisms that have attacked us, such as bacteria.

On the surface of each lymphocyte there are receptors that enable them to recognize foreign substances. These receptors are very specialized and only match one specific antigen. To understand how such specific receptors work, think of a hand that can only grasp one type of object, for example only an apple. Such a hand would be a true master at picking apples, but it would be unable to grab anything else. In our body, such a single receptor would correspond to the hand that captures its "apples". Lymphocytes travel throughout our body until they encounter an antigen that has the right shape and size to match their specific receptor. It seems that perhaps the fact that each lymphocyte's receptors can only match one specific type of antigen would be a limitation, but the body copes with this by producing so many different types of lymphocytes that the immune system can recognize almost any invader.

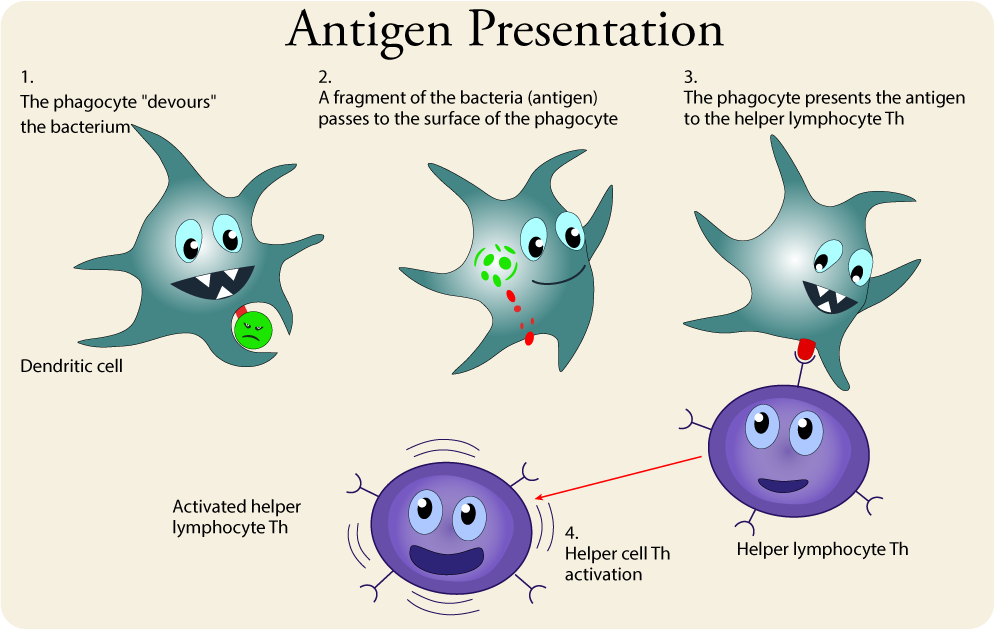

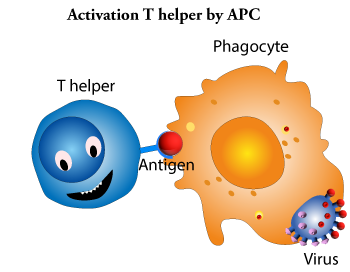

2 Macrophages and dendritic cells belong to the so-called antigen presenting cells. The innate immune system contains cells that detect potentially harmful antigens, and then inform the adaptive immune response about the presence of these antigens. An antigen-presenting cell (APC) is an immune cell that detects, engulfs, and informs the adaptive immune response about an infection. When a pathogen is detected, these APCs will phagocytose the pathogen and digest it to form many different fragments of the antigen. Antigen fragments will then be transported to the surface of the APC, where they will serve as an indicator to other immune cells. Dendritic cells are immune cells that process antigen material; they are present in the skin (Langerhans cells) and the lining of the nose, lungs, stomach, and intestines. Sometimes a dendritic cell presents on the surface of other cells to induce an immune response, thus functioning as an antigen-presenting cell. Macrophages also function as APCs. Before activation and differentiation, B cells can also function as APCs.

Th helper lymphocytes are the main driving force and regulator of the immune system. Their primary task is to activate B lymphocytes and killer T lymphocytes. However, the Th helper cells themselves must be activated first. This happens when a macrophage or dendritic cell that has previously absorbed the intruder moves to a nearby lymph node and presents information about the caught pathogen. The phagocyte presents a fragment of the intruder's antigen on its surface in a process known as antigen presentation. A Th helper cell is activated when its receptor recognizes an antigen. Once activated, the Th helper cell begins to divide and produce proteins that activate B and T cells as well as other cells of the immune system.

Th helper lymphocytes are the main driving force and regulator of the immune system. Their primary task is to activate B lymphocytes and killer T lymphocytes. However, the Th helper cells themselves must be activated first. This happens when a macrophage or dendritic cell that has previously absorbed the intruder moves to a nearby lymph node and presents information about the caught pathogen. The phagocyte presents a fragment of the intruder's antigen on its surface in a process known as antigen presentation. A Th helper cell is activated when its receptor recognizes an antigen. Once activated, the Th helper cell begins to divide and produce proteins that activate B and T cells as well as other cells of the immune system.